How did this become sacred?

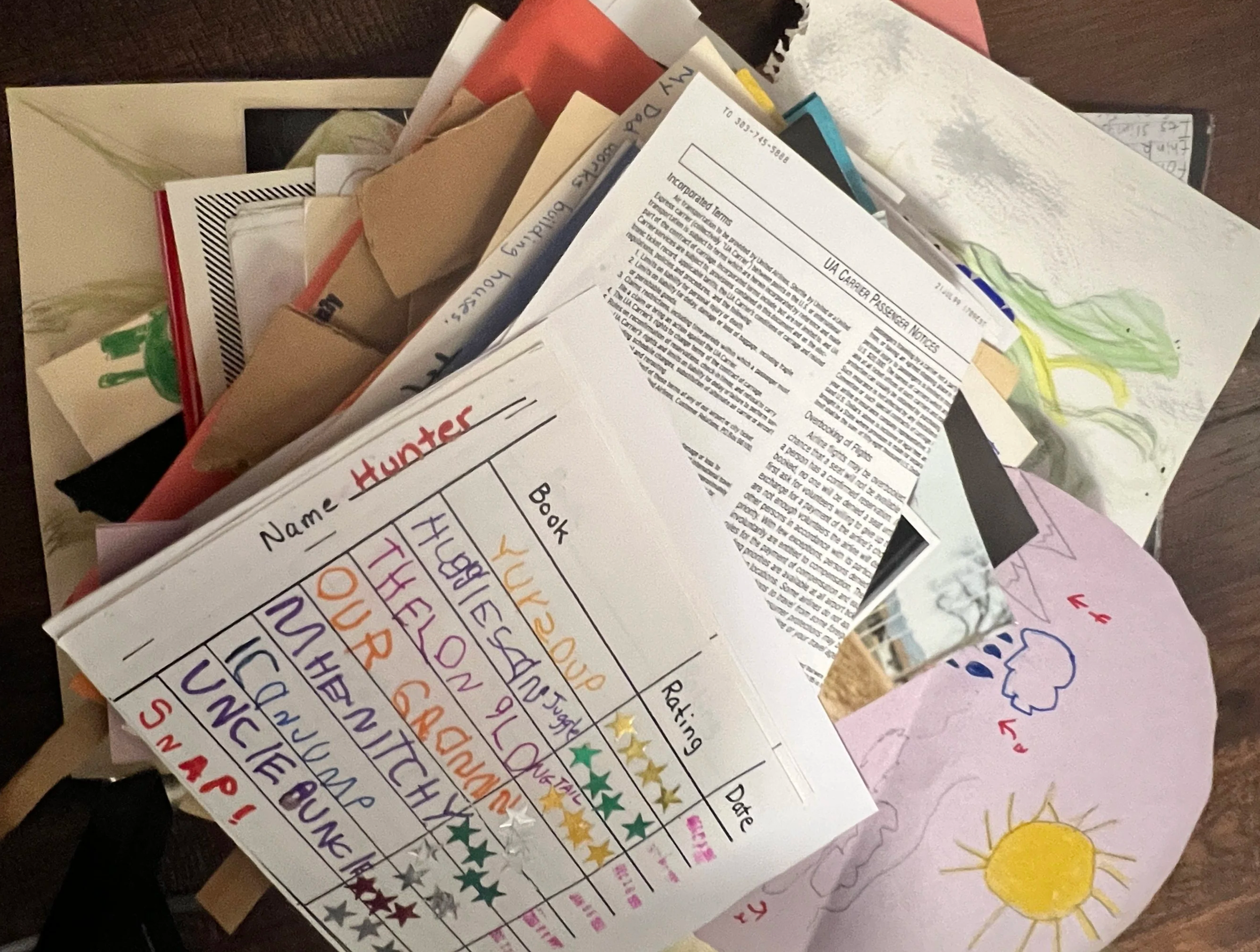

Years ago, my mom asked me to help organize the storage room. Among holiday decorations and suitcases, I found three not-small boxes filled with mine and my brother's elementary and middle school art and school work. After negotiation and tears, we reduced it to one small box: 'Cole and Hunter's school and art that Mom wants to keep for some insane reason,' I wrote in Sharpie.

The box remained unopened until October 2024, a year or so after she died.

Decisions Delayed, Grief Displayed

“Do you want me to send you any of this stuff?” I asked my brother.

He laughed. “God, no. ” Understandable. He lives on the other side of the country, has children of his own.

My dad’s response wasn’t much different.

He had saved his mementos of our childhood when he and our mom divorced decades ago.

I pulled everything out and stuffed it on a shelf, alongside the lopsided rope “vase” I’d made my mom in grade school, an effort to mimic the southwestern pottery she loved, and something my brother made with his initials all over it, something I’d deal with later.

Surely I’d be able to throw it all out eventually.

How We Keep What We Keep

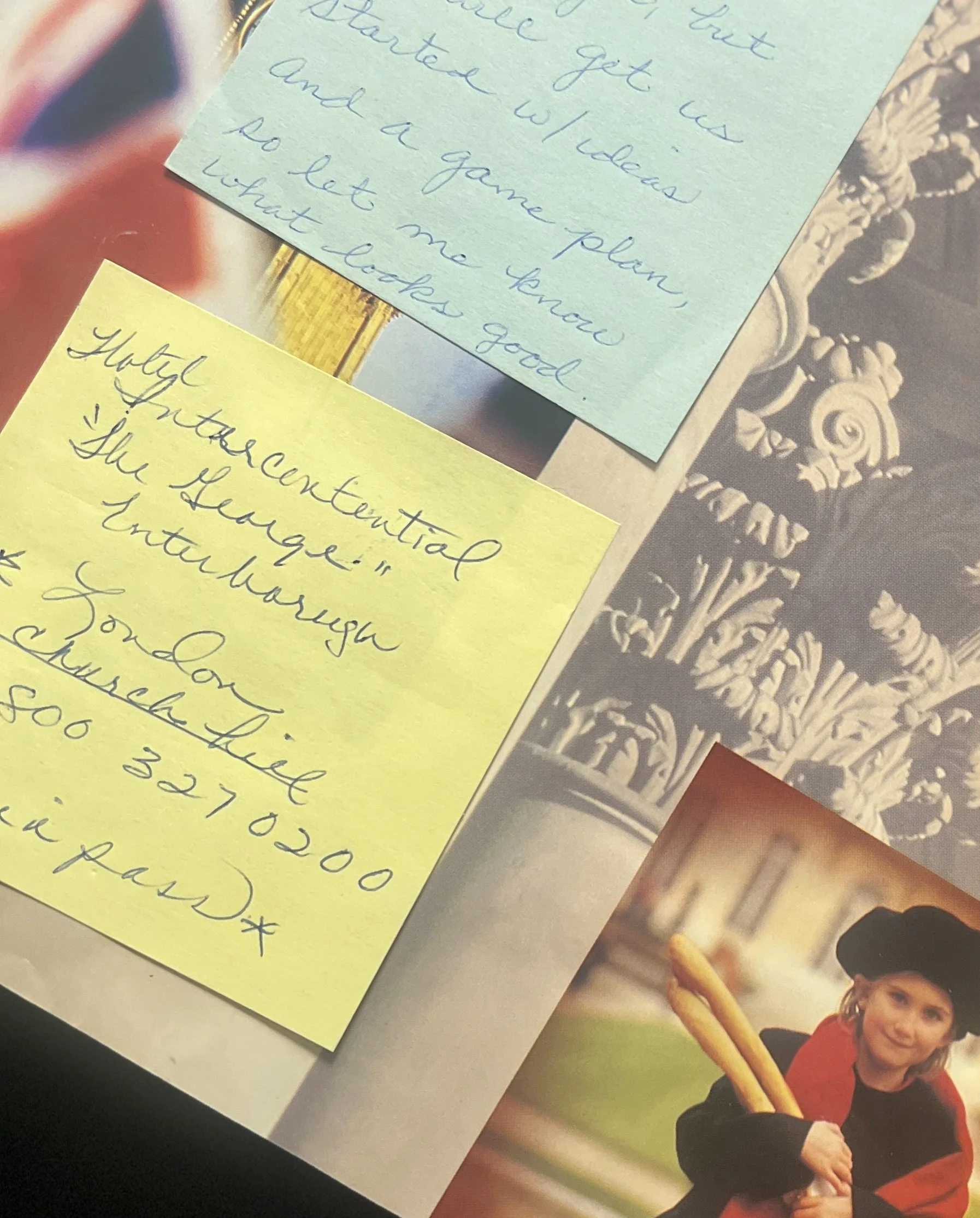

Some things are easy to decide what to do with: certain items of clothing, jewelry, higher value art. It’s not that the stories of how people keep and use or display those items aren’t wonderful and moving, but I haven’t had to think terribly hard about what to do with my mom’s jewelry, while finding a note she wrote reminding herself to pick up something from the store stuck between the pages of a book? That I could agonize over for days.

Post-Its with my mom and grandma’s handwriting.

What Matters to You, Matters to Me?

This thought echoed in a conversation I overheard when my cousin Eliza called my dad. Her father had recently died, in his late 90s, only a year after her brother Stephen died from cancer. Their mother had been gone 20-some years. 'I'm finding all this stuff they kept from when we were in kindergarten in France. What am I supposed to do with it? It must have meant something if they kept it for 50 years.'

How do we decide what’s important? When does an object go from a thing, to something precious? When we were nomadic people, we had little choice as to what we could carry—what we needed to survive, to worship. The choice to carry something spoke volumes: I will carry this because it matters, even as space is limited, and miles are long.

It’s not so different now. Millennials are less likely to own a home than our parents and grandparents, and many live in smaller spaces than previous generations, meaning we don’t have the physical space to keep both family heirlooms, and our own childhood relics. In my most recent move (my third in as many years), I threw out my high school year books. After reviewing the inscriptions, only remembering a few of the names, I couldn’t understand why I’d carried them around for so long.

Throwing these things out can feel like losing someone all over again.

And yet, what am I supposed to do with this stuff?

And So

And that, to make a long story slightly less long, is the tangled root of Refrigerator Reliquary. The idea that the seemingly insignificant can suddenly become monumentally valuable when someone you love dies. The acknowledgement that sometimes we’re faced with the responsibility of managing objects our loved one valued dearly, but we just…don’t. Or can’t. But at the same time, disposing of feels like a betrayal to that person.

Throwing these things out can feel like losing someone all over again. And yet, what am I supposed to do with this stuff?

For now, it’s a rhetorical question.

For now, I will hang on to just a few more things, like this lopsided vase, and a pile of artwork my brother and I created and my mom held on to, and share the story of its creation, and the love my mom had for it.